Aiswarya sasi , a young intern recollects the first death of a patient that she encountered during internship

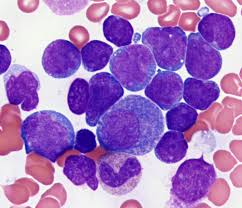

My first posting in the hospital was paediatrics, during the course of which I was posted to the Hematology-Oncology division. That’s where I first met A, a 9 month old baby with B cell-ALL. He was one of many children with ALL in that ward, being the most common childhood leukaemia.

What stood out about A, though, were his temper tantrums. His mother didn’t speak the local language, or even the national language for that matter, so every time she had to be counselled, she would call up her sister who knew Hindi and one of the doctors (including me) would speak to her. Her sister would then patiently translate whatever we had said to her, and she still never looked fully convinced. She was a young mother, not quite understanding the gravity of her child’s illness.

She barely knew how to deal with A. He would scream and yell and refuse to eat, unless she fed him when he was lying down. And quite obviously, there’d be food all over the bed and the aghast nursing in charge would come running and yell at her. Then A would scream and cry loudly, followed by his mother weeping silently not only because she couldn’t understand a word the nurse was hurling her way, but also because she really didn’t know what to do. The senior resident often joked about how she would adopt this child and make him less fussy. Despite all his tantrums and fussiness, we all loved him and his antics.

In the ward, he developed red rashes around his mouth because of his chemotherapy. The poor mother didn’t even know how to ask questions about it. Soon, his platelet count was falling, and he required Single Donor Platelets to be transfused. The blood bank said it would be impossible to arrange for without a donor, and I told my Post Graduate and Senior Resident helplessly. We all sent messages requesting for donors of his blood group to our respective Whatsapp groups. Alas, the lockdown due to COVID19 had begun, and the only people left in the campus were other interns and other faculty and post graduates. The blood bank was also taking all precautions, and was not accepting blood from staff of any department with possible exposure.

My blood group was the same as A’s, so I decided to give it a try. They said that Single Donor Platelets required more blood than usual donations, so they wouldn’t take it from me by virtue of me being female. However, they would be able to take blood and use it for Random Donor Platelets. Given my history of progressive rejection by the blood bank, I shouldn’t have hoped for much, but somehow I was still optimistic. I was thrilled when I found that my weight was above the cut off!! But just as I got hopeful and filled all the forms, they found my Haemoglobin to be 0.4 g% short of the cut off. ‘It’s okay, just take my blood!’ I tried insisting, but to no avail. I came back dejected, but somebody eventually did donate blood for A. That’s when I realized how easy it was to get attached to patients. I had literally spent my whole day thinking about him, bugged everybody at the mess table to donate blood for him, and I kept worrying about whether they had found a donor. We even tried convincing A’s mother (through her sister) to arrange for donors, but even we knew it was impossible for them during the lockdown.

After 5 days, my posting in this division ended and I was back to the general Pediatric wards. On a visit to the ITU (a ward somewhere between the general ward and the ICU for children who need regular monitoring), I noticed that A was now shifted here. He and his mother were both sleeping peacefully on the small bed. I hoped he would be fine, as I went about with my work.

The problem with Pediatrics is when your rotations within the department change and some patients coincidentally follow you. That’s when you develop unhealthy attachments because you get to know them and their illness a little too well. When I moved on to the Pediatric ICU for my next posting, A was there. He had gone into sepsis, and he didn’t look very good. On my first day there itself (and his third day in the ICU) my post graduate said- ‘We’ll keep his discharge summary ready today.’ ‘Oh, he’s going to be shifted back to the ward?’ I asked naively. ‘No, I don’t know how long he has left.’ I didn’t know how to respond to that. Neither did I have the heart to keep his discharge summary ready.

The next day was a very long day. I had the day and night shift in the Pediatric ICU. When I went in the morning, instinctively I asked the PG how A was, and whether he had improved. ‘No he hasn’t,’ she said. Over the course of the day, I watched him deteriorate. His mother was counselled about his condition, and she was in tears. In the afternoon, he was intubated and put on a ventilator. That’s when his mother started breaking down little by little. She said he was thirsty, and that she wanted to feed him water but nobody allowed her to, for obvious reasons. The Senior Resident from the oncology division kept visiting too. She told us about how A’s mother had seen her outside the ICU and kept holding on to her and asking her to do something, because she was a familiar face.

We kept watch on his saturation and electrolyte levels periodically, and things definitely did not seem to be looking up. I went for dinner, and on the way back to the hospital I was telling my friend about how I really hope A makes it, at least through the night. But I got a really weird feeling in the pit of my stomach as I made my way up the stairs. The benches outside the ICU were unusually empty, and there was a lot of noise coming from within the ICU. I ran in quickly, praying against all odds that nothing had happened. But it was over.

His mother was screaming, wailing and violently flinging about her arms. She sat on the floor near his bed and refused to move. The consultants had to call the security to pull her away. My heart sunk. A lay motionless on his little bed.

What haunted me was the fact that I had been there the whole day, but this happened in the half an hour that I had left. But why was that bothering me? It’s not like I could have done anything to save him. Even so. I stared at the baby.

‘Come, we’ll go type the death summary,’ my PG said with a sense of urgency. Within the course of a day, a discharge summary had transformed into a death summary. We sat together, not even acknowledging what had happened and typed aggressively. A’s mother’s loud wails resonated from outside the PICU in the background. The SR from oncology came as soon as she heard the news, and she looked visibly crestfallen, though she didn’t say a word about it.

Will I be as affected by the death of a patient several years into my career? I probably will be. Or maybe it was because I had been seeing him from the very beginning of my posting, like the senior resident who had seen him this entire month.

The way doctors react to death is unique to each doctor, I feel. We don’t learn this in textbooks. Most lose themselves in work, and that’s what I did that night. We typed away until the summary was done. We watched all the formalities taking place, and the body finally being taken away. The wailing stopped, and there was a sudden eerie silence. I now think back to my first ever death in this hospital, back in my second year MBBS when we had just about begun our clinical training. I had seen the patient exactly once the previous day on rounds, and that’s about it. I didn’t know anything about the patient. But the next day, when we went again with the doctor from the Pain and Palliative Medicine department, he had just passed, barely 15 minutes ago. My eyes had welled up and I had taken a minute to compose myself. This time, I hadn’t cried. Was it because I had grown as a doctor over these years of training? Had I become more accustomed to the air of death that inevitably loomed over the critically sick? Or was it perhaps just a chance occurrence? It was too soon to tell.

Would A’s mother have been more at peace if she had given him some water? It would have made no difference to his condition; yet, from her eyes, it was her doing something… anything for her dying son, instead of watching all the machines around him helplessly. I guess again, we’ll never know.

A was my first death as an intern. My eyes tear up a little as I type this out. I can’t even imagine what his mother must still be going through, one month later. I wish her all the strength and hope she needs to tide over these trying times, because that’s all I can do.

Feature image courtesy: Alexander Krivitskiy on Unsplash.

IV stand image courtesy : Marcelo Leal on Unsplash, Hourglass image courtesy: Aron Visuals on Unsplash